Agronomy Update

Jun 18, 2024

Tips for Managing Foliar Disease in Pulses

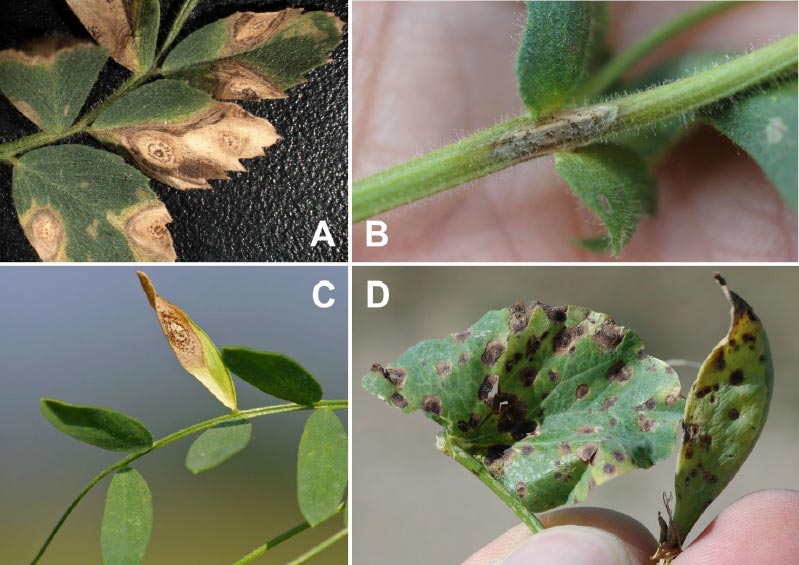

The wet and cool conditions we have been having are ideal for most of the foliar diseases that plague pulse crops and the recent identification of Ascochyta in chickpea already this season is proof of that. There is a lot to keep track of in terms of managing foliar disease in peas, lentils and chickpeas but there are some general guidelines to follow when making a fungicide application decision.1. Proper timing is essential to achieving satisfactory control. These products act preventatively, not curatively, so spraying after symptoms are already severe is not going to save your crop. Even penetrant fungicides are only effective at slowing or stopping infections within the first 24-72 hours after initial infection. There are no visible symptoms during this period. Timing is also specific to the disease being managed and may also differ by crop in some cases. For Ascochyta in pea and lentil (top picture panel C and D) we generally wait until early flowering so that we can get the fungicide into the lower canopy right before it closes. With chickpea you cannot afford to wait until early flowering if you see symptoms (top picture panel A and B). Conversely, control of powdery mildew in field pea is improved by waiting to apply until pod fill (bottom picture).

Picture Credit: Montana State University. Diseases of Cool Season Legumes.

2. Fungicides only protect the tissue they cover. For this reason it is really important that you get good deposition of the product onto the plant, and that you monitor the weather so that you are not applying immediately before a rain event. Exact rain fast periods are not always explicitly stated on the label, and can range from “dry before rainfall” to an hour or more. Generally locally systemic fungicides are more rain fast than protectant fungicides which may wash off (ex. Bravo WS). We add an NIS to improve coverage and use 15-20 gal./ac of water. As the plant grows, the new tissue is not protected so in chickpea for example, repeated applications for Ascochyta management is not unusual in rainier seasons.

3. Fungicide active ingredients are specific to certain diseases. Much like herbicides only control certain weeds, fungicides can be highly specific to the diseases you are trying to control. To complicate the matter, Ascochyta blight in field pea and chickpea is resistant to the Group 11 chemistries and the chickpea pathogen has shown resistance to Priaxor (SDHI) in North Dakota. For example in lentil we want to control Anthracnose but we might also be concerned about white mold this year. These are managed with different fungicides and to control both you would need to apply them as a tank mix. Endura is a great product on white mold (top picture), but poor on Anthracnose (bottom left picture) and Ascochyta (bottom right picture).

With the hot and dry weather pattern we have been in for the past few years, we might have been able to forgo a fungicide application on peas and lentils previously and not seen a noticeable reduction in yield. This year we have the right conditions for disease, so keep an eye on your crop and consider a fungicide application. Disease doesn’t just reduce yield, it can also harm seed quality and be transmitted to your crop via seed and infested residue next season.

Dr. Audrey Kalil, Agronomist and Outreach Coordinator

Controlling Canada Thistle

As our cropping rotations and practices have changed over the years, so too have our methods for controlling Canada thistle. Even when we were mainly growing wheat or durum in a summer fallow rotation, Canada thistle was a little tricky to control. Our best option when we had summer fallow was a practice that became known as the “Hunter Method”. This involved working your summer fallow or spraying your chem fallow one time early in the sea-son and possibly a second time in the middle of the summer, preferably be-fore the end of July or middle of August. Then to leave it alone until around the middle of September, closer to an early frost. Once the days get shorter and the nighttime temperatures get cooler, the plant starts to move all of the energy into the roots and stay in the rosette stage instead of trying to bolt and make seed. That is when we would spray a quart of glyphosate per acre and hope for the best.While it is still common practice to use glyphosate in the fall to control this weed, we are spraying post-harvest now instead of chem fallow or summer fallow. Our other main herbicide option over the years has been to spray any product with the active ingredient clopyralid. One of the main products we would use was Curtail, which has since been discontinued. Products we currently retail which have the active ingredient clopyralid in them would be the stand alone clopyralid product Stinger as well as premixes containing chlopyralid; Widematch, Weld, and Perfect Match. All of these products are all very good on Canada thistle. To control Canada thistle in the spring, we would recommend to actually wait until the plant is at least 8 inches high or at your herbicide timing. We have a better chance of more of the rhizomes being out of the ground at this point. If you spray too early, we will see more come out of the ground after we spray resulting in reduced control.

|

|

Seedling Canada thistle is not really that hard to kill, but once you have a patch established, the root system can be up to 6 feet deep and only about 10% of the root mass will be in the top foot. That is why we don’t want to see this weed neglected. One plant can spread to cover an area three to six feet in diameter in just one to two years. If you end up having to clean up patches of established plants, it could take you up to 3 to 5 years. I know everyone wants to keep their options open for pulse crops, but you are only compounding the problems by planting pulse crops into fields that you know you have established patches of Canada thistle. If nothing else, spot spray the spots of Canada thistle in your pulse crops too and eliminate the Canada thistle plants. You will not have any peas or lentil in those spots when spraying clopyralid, but if you leave the Canada thistle alone, it will out compete the crop and you will not have much there to begin with. Clopyralid is labeled for most cereals, canola, corn, and flax, but please check labels or ask one of our agronomists on which specific products to use on which crops and be sure to be aware of the plant back restrictions.

John Salvevold, Agronomy Division Manager, CCA

Nutrition at Herbicide Timing

June can be a tough month for crops and it typically coincides with when we are doing our in-crop herbicide application. In recent years, hot temperatures and long sunny days has stressed the crop. This year we have had moderate temperatures and when the wind lets up, we’ve had some good spray conditions. However, the volatility in the weather between high and low temperatures, high winds, and hard rains has stressed some crop even with the excellent moisture we’ve received. Herbicides applications could also lead to some stress related issues on our crops. This is much more likely during hot, dry weather, but is still something to be on the lookout for this year.To help combat crop stress and add a boost of fertility during herbicide application you can add a micronutrient like Re-Leaf®. This will help keep the plants green during the hot and sunny conditions that the end of June and July can bring. Re-Leaf® has formulations for pulses, soybeans, canola, and cereals with use rates ranging from 1-2 quarts per acre. This isn’t a replacement for starter fertilizer going down the drill next to the seed, but an additional application of micronutrients will be an added benefit to help reach yield potential. Something small like applying Re-Leaf® to add another 10-30% phosphorus mixed with your herbicide at in-crop application will help the roots grow deeper and stronger so that the plant is better able to combat stress later in the season.

Austin Semenko, Williston Location Agronomy Manager

Copper Fertility in Wheat—Update

Reading my previous article on copper fertility in wheat I am guessing many of you may have thought, “Yeah I’ll probably just pass on that this year.” One of my consulting clients felt the same way, which is totally fine. Later on in the season, I noticed patches of yellowing and necrotic tips on the flag leaf in a winter wheat field of this client (see pictures below). So, I did what any good agronomists would do and busted out my soil probe and went out to take soil and tissue samples from the normal looking areas and the spots that looked abnormal with the yellowing/necrotic flag leaf tips.The results showed that copper was deficient in the abnormal looking areas, and there are some root causes which explains this deficiency in the crop:

- Soil extractable copper is below 0.5%

- Soil organic matter is below 2%

- Soil pH is VERY Acidic (a big reason a lot of things are out of whack) High nitrogen content in the leaf tissue in Cu deficient spots.

Could this field have been a good candidate for foliar copper earlier in the season? Our answer is yes, and we will be addressing this in the future when wheat is planted here next.

Kyle Okke, Crop Consultant, CCA

| Cu Deficient Tissue: 1 ppm Soil: 0.37 ppm  |

Cu Sufficient Tissue: 4 ppm Soil: 0.72 ppm  |

Root Rot is Making an Appearance

I scouted a pea field last week with some yellowing areas (left picture below). When I dug up plants in the yellow patches and compared them with plants in the green areas there was a stark difference between the roots of healthy plants and symptomatic plants (right picture below). Diseased roots were brown instead of white, the stem was shrunken and brown and there were few to no nodules present. I don’t need a test to tell me there is root rot in this field, but I plan to send in the root samples to the National Agricultural Genotyping Center to see if the problem is due to Aphanomyces, Fusarium or something else. If you are seeing symptoms like this in your field, dig up plants from healthy and diseased areas and you should be able to tell if there is root rot present. The wet conditions this year are conducive to root rot, but it is important to eliminate other causes of yellowing (nutrient deficiency, lack of nodulation etc.). Fields with Aphanomyces should not be planted to peas or lentils again for a minimum of 5 years (6 year rotation) to prevent the pathogen from spreading and getting worse. If you have any questions please feel free to reach out. Dr. Audrey Kalil, Plant Pathologist/Outreach Coordinator

|

|